Greek philosopher Aristotle once wrote, “Often when one is asleep, there is something in consciousness which declares that what then presents itself is but a dream.” But what does this mean? Well, Aristotle wanted to find out why humans dream and in doing so, accidentally discovered what is known as a lucid dream. Lucid dreams are dreams in which the dreamer recognizes they are asleep and so they gain consciousness within the realm of the dream. When Aristotle referred to “…something in the consciousness…”, he referenced the perception and recognition leading to a lucid dream. He concluded that it results from the sensory organs continuing to function while the body sleeps. It’s known that this is not the case, as the stimulation doesn’t quite reach perception. Although theories suggest dreams simply consolidate memories, analyze events, and represent hidden meanings, the true nature of it all remains unknown.

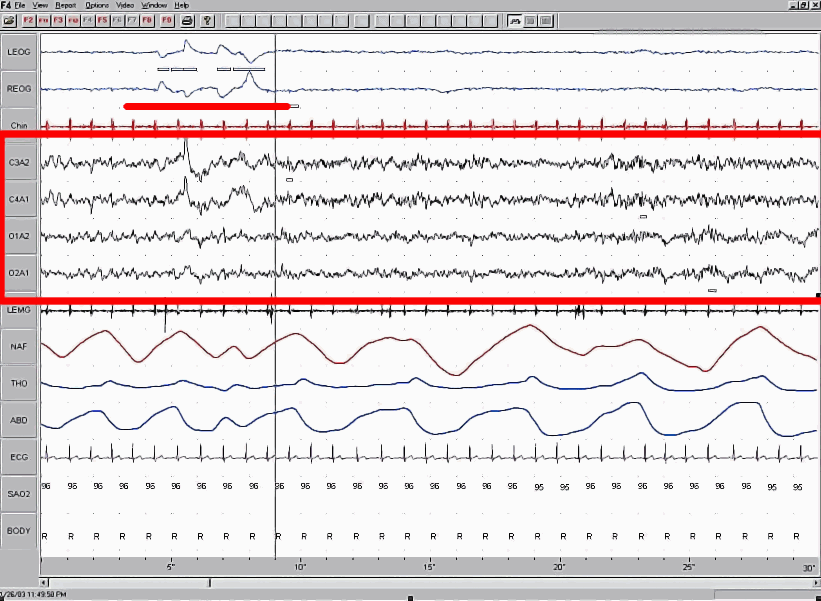

In 1913, Van Eden wrote that the purpose of lucid dreaming was to “…attempt different acts of free volition”. He essentially says that exploration of the dream realm by using the free will gifted to the dreamer upon perception of a dream is the whole point of these special dreams. The problem is there was no evidence that this was real. For all anyone could tell, it was a huge joke made by an inside community to troll psychologists and scientists alike. This would all change when in the mid-70s Dr. Keith Hearne paired up with a person who could lucidly dream, or Alan Worsley. Lucid dreaming happens in REM sleep. REM sleep is commonly defined through the body’s rapid eye movement that occurs during this part of the sleep cycle. Through the use of predetermined eye movements, Worsley could direct his eyes to follow the movements that were agreed upon during a lucid dream, confirming to Dr. Hearne that during REM, he genuinely was lucid.

Lucid dreaming can be detected through a few common signs. Physiologically, the autonomic nervous system and the frontal and front lateral regions are more active. Acetylcholine levels are also raised, which influences our memories and brain functions. One big note is that the parietal lobe, bilateral precuneus, and occipitotemporal lobes, are usually deactivated during REM sleep, and suddenly become active during lucid dreams (Stumbrys 3). These areas help someone understand their surroundings and the world around them, which correlates to the idea that when a person is consciously aware of what is happening in their dreams, they are processing the world around them. Finally, some voluntary actions/functions in lucid dreams can cause similar physiological reactions. For example, breathing faster in a lucid dream can cause a person to begin to breathe faster in real life. When hooked up to an EEG machine, people experiencing lucid dreams tend to show REM-like activity of lower delta and theta waves but a higher-than-normal REM level of gamma bands (Voss, et. al.). In Voss’s experiment, twenty students were trained to induce lucid dreams. Through Worsley’s method of verifying a lucid dream through eye movement, six of the students were able to experience a lucid dream. With the information from the EEG machine, there were clear different coherence patterns between waking, REM sleep, and lucid dreaming.

One interesting study by Dr. Fariba Bogzaran in the 1990s shows how lucid dreaming is part of a subset of psychology, called transpersonal psychology. This type of psychology aims to integrate spiritual practices and ideas into human experiences and thoughts. This can be practiced through meditation, hypnotherapy, and dream work. In other cultures, older traditions such as Tibetan dream yoga and Shamanism use lucid dreaming to develop ideas further. Bogzaran had a group of 77 people come together to try and experience the Divine within their dream, with about a 45% success rate. The most notable part of this experiment was that the Divine representation changed depending on the dreamer. Those who believed in a personable form of the Divine dreamt of them in that personalized form, while those who thought of the Divine as a form of energy or a concept dreamt of it as such. The dreamers attempted to have a transformative and spiritual experience in these dreams, searching for guidance (Stumbrys 8). This is known as hyperspace lucidity. It shows that these special dreams can be used as a tool for transpersonal therapy. They can help facilitate inner therapeutic work such as growth and coping with fears. There’s a present link between this and meditation practice. There’s continuity with meta-awareness, perception, projection, and comprehension in the sleep and wake cycle.

Lucid dreaming is a peculiar phenomenon that is yet to be completely understood. It can be a transformative and imaginative experience or a fun way to explore new possibilities. Anyone can do anything. The dreamer is the creator and that’s what matters the most when it comes down to what exactly lucid dreams are.

Sources

Baird, Benjamin, et. al. “The cognitive neuroscience of lucid dreaming.” Science Direct, 8 May 2018, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0149763418303361. Accessed 24 September 2024.

Stumbrys, Tadas. “BRIDGING LUCID DREAM RESEARCH AND

TRANSPERSONAL PSYCHOLOGY: TOWARD

TRANSPERSONAL STUDIES OF LUCID DREAMS.” Research Gate, 1 July 2018, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tadas-Stumbrys/publication/333237329_Bridging_lucid_dream_research_and_transpersonal_psychology_Toward_transpersonal_studies_of_lucid_dreams/links/5ce3b568a6fdccc9ddc15c9f/Bridging-lucid-dream-research-and-transpersonal-psychology-Toward-transpersonal-studies-of-lucid-dreams.pdf. Accessed 26 September 2024.

Voss, Ursula, et. al. “Lucid Dreaming: A State of Consciousness with Features of Both Waking and Non-Lucid Dreaming.” National Center for Biotechnology Information, 1 September 2009, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2737577/. Accessed 2 October 2024.

Leave a Reply